Memory Space

nostalgia and the ambivalence of neighborhood change

I’m writing to you from the middle of a thought.

I’m thinking about the colonial conceit undergirding the concept of neighborhood change. “Colonial conceit,” meaning the presumed authority to dominate and takeover land through exploitation, extraction, and displacement of people already living there. “Neighborhood change,” meaning gentrification: a municipal and industry strategy of attracting affluent white people to working-class black and brown neighborhoods to build a tax base, boost commercial activity, increase safety, make a so-called despressed area more desireable, and so on and so forth. This process has become so normalized in cities big and small that to name it feels passé, too simple, so much a part of the way of things that witnesses no longer register the assault.

We have a lot of scholarship and cultural work set in gentrifying landscapes, including recent ones I keep close on my desk or in my mind as I work on my own research: Brandi Thompson Summers’s Black in Place: The Spatial Aesthetics of Race in a Post-Chocolate City (2019), Samuel Stein’s Captial City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State (2019), Joe Talbot’s and Jimmie Fails’ film “The Last Black Man in San Francsico” (2019), Mercy Romero’s Toward Camden (2021), Toya Wolfe’s Last Summer on State Street (2022), and A.V. Rockwell’s film A Thousand and One (2023). I write this list here, in part, to remind myself of the syllabus that needs teaching once I have a little distance from the project. In the meantime, please indulge me on the following archival material I would have assigned my students.

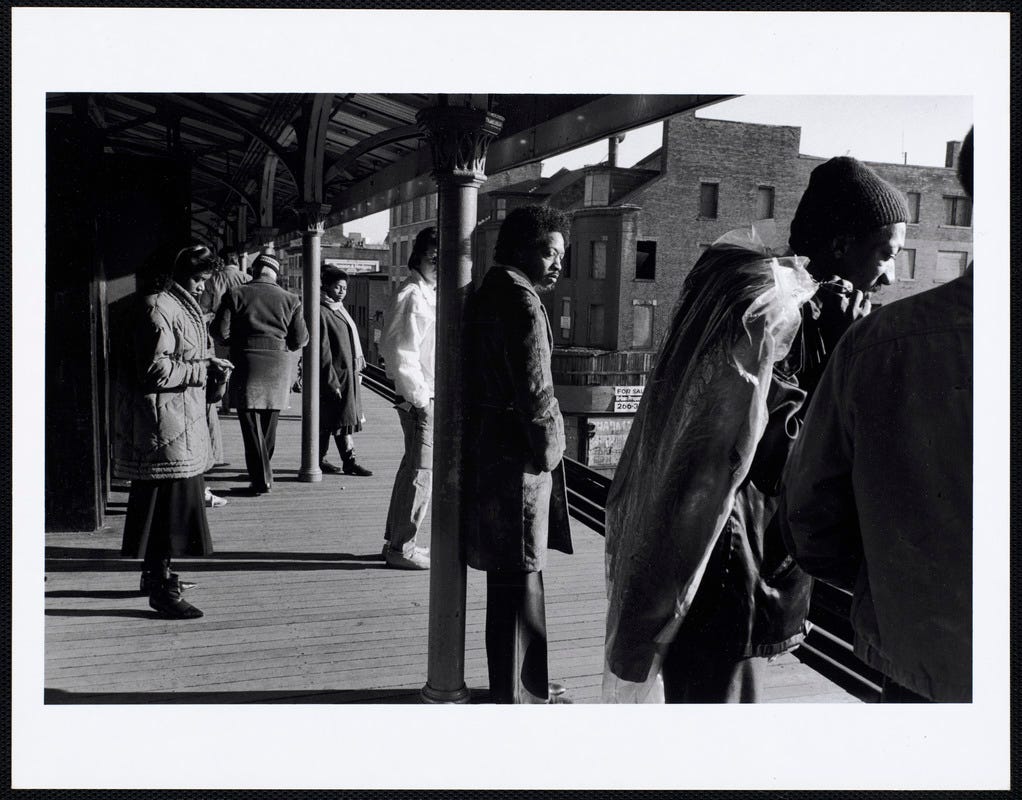

The human costs of gentrification are palpabale in the memories of elders displaced or proximitate to displacement throughout the twentieth century. They endured slum clearances and urban renewal demolitions in the 40s and 50s, organized for public housing and community development in the 60s and 70s, and by the 1980s, got pushed and priced out of the same neighborhoods they fought to protect. Today, I share with you part of a poetic reflection from Patricia Beckles, a Black woman who lived in Boston’s South End and Roxbury neighborhoods, and who recalled childhood memories of the elevated train. The elevated included three stops that were central to Black Boston mobility between and beyond the neighborhoods, though another elder said it wasn’t wise to venture much further than those three. The “El” was demolished in the 1980s as part of the city’s revitalization efforts and replaced with the below-ground Orange Line train more central to Boston’s buisnesses, hospitals, and universities. It wasn’t until 2002 when the Silver Line—part bus, part rail—reconnected some of those stops along the “El” that had once served working-class Black, Brown, and Asian residents. I found Patricia Beckles’ reflection on the “El” in The Boston Memoir Project’s digital archive. Her writing is tender and beautiful, and captures the dissonance of losing a sense of home for the sake of so-called progress.

PATRICIA BECKLES: PROGRESS

From “The Boston Memoir Project”, a collaboration between the City of Boston Elderly Commission and GrubStreet Center for Creative Writing

“I. The Elevated Trains

I am sleeping and I feel warm and safe. I am in my father’s arms, and I bury my nose deep into his shirt, and I can smell his own personal smell and I know nothing can harm me, when all of a sudden I hear this terrific shriek; it is ear piercing; it snaps my eyes open and for a few seconds I feel as if I am falling and my whole world has ended.

I cannot recall my first ride on the El, but ever since I can remember there has been this dark structure. It was as if God had permanently stretched his palm over the sun. These giant cars would go by periodically, and although the ground did not shake I could feel the vibration through my feet. The sound of the train racing by was so loud you had to shout to be heard, and even then sometimes you could scream at the top of your voice and still, no one could hear you. The tracks that appeared to be suspended in space seemed to stretch for miles. There were curves where the train tilted to one side and I always thought the train would tip over and fall to the ground. Going around these curves, the wheels would screech so loud like brakes grinding on metal and I always felt that a disaster was about to happen.

This structure was built in the 1920s, and all my life I heard they were going to tear it down. Finally in the eighties they did tear down the El, including the beautiful stations like Dudley, Northampton, and Dover. These magnificent stations with their high mansard copper roofs, sturdy wooden floors, and miles of curved wrought iron railings, were all torn down and thrown away.

In its place I can now see the sun shining down on Washington Street. I can see that it is truly a boulevard, with four lanes of traffic. Gone are the neighbors who used to socialize in the shelter of the El. Although God has now removed his palm from the sun, and I no longer fear the trains falling from the sky, some days I can still hear the roar of the trains and that shriek of the wheels in my head, and I do not like progress.”